Over the past six years, the Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center has been enhanced with a rich collection of Indigenous works donated by collector Edward J. Guarino. With his vast knowledge of the works and close relationships with the artists, Mr. Guarino has brought his expertise to Vassar and significantly contributed to the growth of its Native American Studies program. From this relationship, Assistant Professor of English and Native American Studies Molly McGlennen developed a course that explores alternative approaches to the study and presentation of Indigenous art by utilizing a set of important contemporary Inuit works from Mr. Guarino's collection. The course, AMST 282: Folklore, culminated in Decolonizing the Exhibition, a student-curated show of 15 works on paper by major Inuit artists.

This exhibition was held in the Focus Gallery, Spring 2014.

“It’s very different down here than it is up North [in reference to a southern Canadian city]” —Kavavaow Mannomee

Kavavaow Mannomee spent his early life in Brandon, Manitoba, where his mother was hospitalized for tuberculosis. From a young age, Mannomee navigated cultural intersectionality, which is reflected in his manipulation and indigenous contextualization of Western iconography in this piece. He began his artistic career as a printmaker, meticulously cutting in stone the works of other artists. Mannomee started selling his own drawings in the mid-1990s. In his oeuvre, Mannomee is known to play with scale and surrealism; such experimentation has earned him a reputation for creating whimsical work, but work that also deals with a wide variety of social and political influences. Such tropes point to Mannomee’s place among a younger generation of Inuit artists who are undermining stereotypes through staunchly contemporary (and oftentimes political) works.

If you'd like to read more from Kristina Arike ’14, Claire Fey ’15 and Isaac Lindy ’14 regarding this work click here.

“I am happy to continue making drawings of animals and humans having a good life and enjoying themselves. It disturbs me when I see images of people drinking and committing suicide; I want to focus on more positive images.” — Kananginak Pootoogook

Kananginak Pootoogook, nicknamed the “Audubon of the North” is known for his realistic portrayal of Arctic birds and wildlife. A respected elder of his community, Kananginak was a prominent artist of the Cape Dorset Cooperative and became well-known for his use of many different mediums, including lithography, painting, etching, and stone sculpture, gaining notoriety beyond the Inuit art world before his recent death. Kananginak celebrates the lifestyle of the Cape Dorset community, portraying the slow and almost imperceptible changes made as they adapt to colonial influence. This piece is the second largest piece he ever completed, as well as one of his last works, which emphasizes the importance of the hunt to past and present Inuit lifestyle.

If you'd like to read more from Kamaria Mion ’14 and Alex Schlesinger ’14 regarding this work click here.

”I taught myself everything. Nobody taught me anything. I had no teacher. I learned on my own.” — Itee Pootoogook

In these two prints, Itee Pootoogook depicts the Arctic landscape with powerful simplicity and deft precision. On the left, sunlight floods the summer seascape, radiating from the page in shades of green and yellow. Hazy summer stands in direct opposition to the cool clarity of the winter print on the right, in which the central sliver of blue hints at the endlessness of the Arctic Ocean. Pootoogook’s geometric arrangement of color effortlessly makes the viewer imagine the reality of these abstracted landscapes. The viewer is positioned as if looking at the landscape through a camera lens, a common theme in Pootoogook’s work, who often uses photographs as inspiration.

If you'd like to read more from Nicholas Corda ’14 and Pilar Jefferson ’15 regarding this work click here.

“When I start to draw I remember things that I have experienced or seen. Although I do not attempt to recreate these images exactly, that is what might happen. Sometimes they come out more realistically but sometimes they turn out completely different. That is what happens when I draw.” — Shuvinai Ashoona

Coming from a long line of artists, Shuvinai Ashoona began drawing around the age of 25 in a time of significant transformation in the region. Her work, like many of her peers’, portrays these changes through means which reflect concurrent changes within the Inuit artistic tradition.

If you'd like to read more from Maggie López ’14 and Jesse Peters ’14 regarding this work click here.

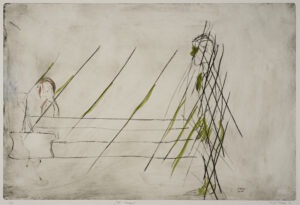

Jamasie Pitseolak (Inuit, Cape Dorset, Canada, b. 1968), The Student, 2010 , Hand-painted dry-point etching, 2/15, 31.5 x 44 inches, Reproduced with the permissions of Dorset Fine Arts

Jamasie Pitseolak (Inuit, Cape Dorset, Canada, b. 1968), The Day After, 2010, Hand-painted dry-point etching, 2/15, 19.5 x 15 inches, Reproduced with the permissions of Dorset Fine Arts

“I had to burst the bubble. And when it did, it just broadened my vision of where I want to go from there.” — Jamasie Pitseolak

Jamasie Pitseolak’s family consists of many artists, especially carvers, who have all influenced his body of work. In his beginnings as an artist himself, Pitseolak participated in traditional forms of sculpture, with regard to specific images and media. However, he did not receive sufficient personal and artistic satisfaction through these modes, which then compelled him to move beyond and explore alternative themes, such as in The Student and The Day After.

In this pairing , Pitseolak moves away from carving and changes his choice of medium to that of a work on paper. Through a dialogue between the two works, he explores his personal experience of abuse in the Canadian Indian Residential School System. These colonial schools were founded with the intention to annihilate Indigenous existence. In this genocidal process, Indigenous children were forcibly removed from their home communities in order to eradicate their ‘Indianness.’ Often, non-Native authority figures targeted them with physical, mental, and sexual abuse. In both his carvings and these two drawings, the artist, as he has stated, creates the works of art for himself – he’s “not doing it for anyone else.” While he previously typically made art as a means of personal enjoyment, The Student and The Day After stray away from that practice and serve to grapple with this traumatic past, his reality – the colonial reality.

If you'd like to read more from Maggie López ’14 and Jesse Peters ’14 regarding these works click here for The Student and here for The Day After.

“I remember while I was there, the nuns wore black with white hats to go with the uniforms. I don’t know if the patients are still there. I did not enjoy my stay at the hospital at all because I remember being afraid of those nurses.” — Pitaloosie Saila

Upon suffering a traumatic accident during which she broke her upper back, Saila was evacuated from her Inuit community by a visiting Canadian official and his wife, a nurse, to Southern Canada. She became part of a larger, forcible displacement of Inuit peoples moved to southern hospitals as a result of the Canadian government’s quarantine of Inuit during a tuberculosis outbreak between 1950 and1957. Having spent much of her young life separated from her homelands, Saila drew on her memories from her time away from her community to create an eerie triad of some of the “types” of non-Indigenous peoples the artist encountered (in this case, a nun, a nurse, and a fancy lady).

If you'd like to read more from Kristina Arike ’14, Claire Fey ’15, and Isaac Lindy ’14 regarding this work click here.

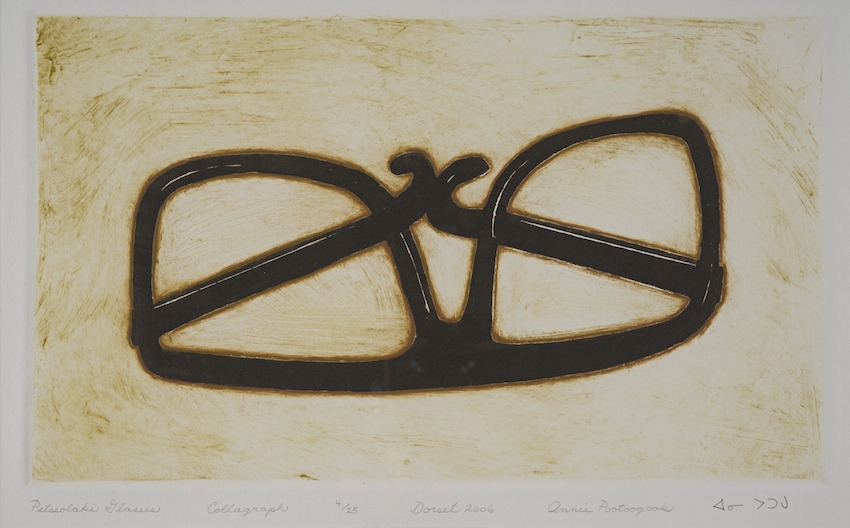

“I used to go see my grandma drawing. They used to talk about what they are doing about life in the past. She used to tell the stories that came with the drawings and those were true stories. I wish I was born in the past. I would know in the traditional ways. I only know by my mom’s drawing and my grandma’s drawing. They knew the past. They are lucky. If I was in the past, I would draw it, too. But I’m not from the past. I didn’t see any igloos in my life. Only today: Ski-doo, Honda, house, things inside the house. That’s only I see, today. I see and I do. What I see, I do.” — Annie Pootoogook

In her drawings and prints, Annie Pootoogook often depicts her late grandmother and influential artist, Pitseolak Ashoona, wearing her signature black-rimmed glasses. In this abstracted still life, the isolated glasses serve as an emotional and storied portrait of their owner. As a child, Pootoogook often visited her bedridden but still drawing grandmother, who was influential in the formation of her representational style and in her development as a third-generation artist. In contrast to earlier portraits, Pootoogook has removed the figure and replaced it with a symbolic object, implying Pitseolak’s bodily absence while still representing a familial essence.

If you'd like to read more from Leighton Suen ’14 and Logan Woodruff ’14 regarding this work click here.

“Of the younger generation of Inuit artists, Siassie Kenneally presents the familiar and even the mundane from a unique perspective. Not unlike Georgia O’Keeffe who made us see flowers in a new and exciting way, Siassie has the ability to make us see loveliness in unexpected places.” — Edward Guarino

Siassie Kenneally cites her entire family as a large influence on her work. Growing up in a family of artists, it is hard to claim otherwise. From birth, she was surrounded by the work of her father, a carver, and her mother, a prominent graphic artist. Kenneally learned early on from her father the importance of taking advantage of their time together and so began to learn from him to advance her own skills.

If you'd like to read more from Kamaria Mion ’14 and Alex Schlesinger ’14 regarding this work click here.

“When I start to draw I remember things that I have experienced or seen… Sometimes they come out more realistically but sometimes they turn out completely different.” — Shuvinai Ashoona

At first glance, one might be tempted to erroneously attribute the depicted circle of harmony among the assembled creatures to a story from Inuit mythology. However, this vivacious and stunningly colorful drawing demonstrates Shuvinai Ashoona’s personal creativity and dark imagination more so than conforming to outside expectations of Inuit art. Ashoona is known in the art world for her detail-oriented and dream-like drawing style. Ashoona credits television shows, as well as her memories, as sources of inspiration for her works. Although many of her representational drawings of tents and natural landscapes evoke Inuit community and history, much of her art is comprised of surrealistic, fantastical images that flow from her imagination onto the canvas.

If you'd like to read more from Leighton Suen ’14 and Logan Woodruff ’14 regarding this work click here.

“I love that place I left as an 11-year-old. I returned in 1994. It brings me back to my roots. I see family there that are no longer here.” — William Noah

Noah renders contemporary Inuit experience through multiple perspectives of a twenty-first century char fishing expedition, suggesting Inuit mobility and continuation in the Canadian arctic. Challenging the ethnographic photographs of Edward Curtis, who intended to capture a “dying race” by chronicling a colonial expectation of Native American cultures, Noah disrupts this dominant and ubiquitous iconography by reinterpreting the medium and its use. He tells a story of Inuit adaptation and continuance exclusively from his Indigenous perspective, using a style reminiscent of photography and collage.

If you'd like to read more from Clara Cardillo ’15 and Nick Veazie ’13 regarding this work click here.

“Sometimes the pencil is stronger than I am.” — Shuvinai Ashoona

Aujaqsiut Tupiq is both representational and abstract. The work is intentionally ambiguous because it is not clear if the viewer is looking at the tent ceiling from the inside or outside while an anonymous figure is seen either entering or leaving the tent with only an arm and a leg in the doorway. The tent glows with a warm light that suggests the activities happening within the home, but the mysterious pictorial space prevents the viewer from deducing a single understanding of the scene. Representation and abstraction coexist in Aujaqsiut Tupiq: representational in that it presents identifiable forms and abstract in the cropped view of the tent and the ambiguous use of space.

If you'd like to read more from Aaron Jones ’16 and Caroline Winkeller ’14 regarding this work click here.

“I would borrow money from my mother to go to the movies because she did a lot of work with her sewing and drawing. When I asked her for money, she would scold me, telling me that I should draw. I would say, ‘You never had a hard time with money,’ and I would tell her ‘I don’t know what to draw.’ She would scold me again and say, ‘If you can draw a person you won’t have a hard time getting money for the movies‘.” — Janet Kigusiuq

The torn, criss-crossing pieces of paper appear chaotic at first, but under closer examination reveal depth as light illuminates the layers of colors. Janet Kigusuiq’s overlapping polygons suggest multiple viewpoints, or viewing moments, by obscuring the distinction between land, water and sky. The undulating blocks of color can be seen as referencing time in the same way light plays tricks on the landscape throughout the course of the day and the season in the arctic.

If you'd like to read more from Clara Cardillo ’15 and Nick Veazie ’13 regarding this work click here.

“There is no word for art. We say it is to transfer something from the real to the unreal…” — Kenojuak Ashevak

Renowned Inuit printmaker Kenojuak Ashevak’s work Animals Out of Darkness brilliantly combines her signature artistic style and her unique worldview as an Inuit woman living in Cape Dorset, Nunavut. In this print she intertwines birds and animals in pictorial space, their bodies flowing across the page from right to left, creating a sense of movement. The mobility of Kenojuak’s creatures combined with the gradient of colors suggests an important narrative that brings the Inuit the promise of a summer. Her distinct use of birds is a theme seen throughout the entirety of her career, and she commonly depicts abstract animal shapes in many of her prints. She transforms these animals into creatures from her imagination – giving rabbits seal fins and seals bird feathers, adding to the overall sense of movement in the print. The flowing nature of her prints is also often due to the fact that while drawing the original outlines she does so without lifting her pencil.

If you'd like to read more from Nicholas Corda ’14 and Pilar Jefferson ’15 regarding this work click here.

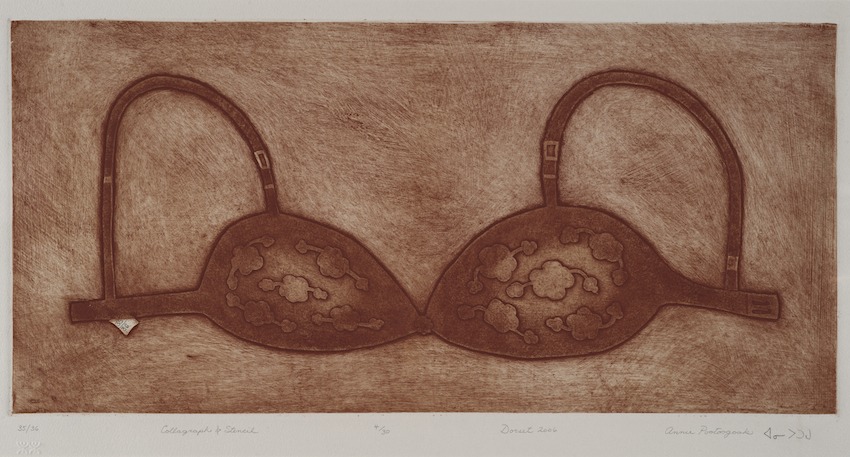

“I never thought that this is [a] traditional Inuit way, [rather] this is [a] white style. I never thought about that because I just draw what I see.” — Annie Pootoogook

35/36 confronts contemporary Inuit femininity and sexuality, subjects rarely depicted in Inuit art, through the isolation of a single red bra. Inuit prints often isolate objects by traditionally depicting seals or fish, important aspects of Inuit life; however, in this work, a bra floats in an ambiguous pictorial space and its details are not minutely rendered. Because of the spatial ambiguity and the object’s flatness, the bra can be understood as a symbol or pictograph. In replacing a traditional subject with a contemporary and sexually charged object, 35/36 forefronts Inuit femininity as an issue relevant to Inuit culture. The isolation of an everyday object and the manipulation of color and form also echoes North American Pop art while revealing an explicitly Inuit narrative. Daughter of Napatchie Pootoogook, and granddaughter of Pitseolak Ashoona, two well-known Inuit artists, Annie Pootoogook began making art in the late 1990’s with the support of the Kinngait Co-operative.

If you'd like to read more from Aaron Jones ’16 and Caroline Winkeller ’14 regarding this work click here.